Interview

Interview

![]() Part 1: Continually seeking what lies at the roots of Noh

Part 1: Continually seeking what lies at the roots of Noh

![]() Part 2: Following the path of apprenticeship

Part 2: Following the path of apprenticeship

Interviewer: Takahiro Uchida, the-Noh.com / Photos: Shigeyoshi Ohi

Part 2: Following the path of apprenticeshi.

Games with his grandfather give shape to Gensho’s career as Noh actor

Uchida: Could you tell us a little about the different stages of your career in Noh, starting with your training as a child actor?

Gensho: My first stage appearance was at the cherry blossom viewing party in Kurama-Tengu; I was three years old. I’m the only son, and my father (Rokuro Umewaka LV), determined to get me involved in Noh in some shape or form, used every trick in the book to coax me onto the stage. At that time, my grandfather (Minoru Umewaka II, Rokuro Umewaka LIV) had retired, though he was still appearing on stage, and he had me practicing every day.

It didn’t feel like practice, mind you. He taught me about the stage through games. My grandfather died when I was eleven, but by that time I’d learned 99 percent of what I needed to know.

Uchida: Ninety-nine percent!

Gensho: My father entrusted the whole undertaking, more or less, to my grandfather. If you practice under a range of different people in childhood it only leads to confusion. My father would probably have liked to have been able to teach me the stylized movements of hands and feet himself, and I applaud him for leaving everything in the hands of my grandfather. My grandfather was of the belief that the head of the household should watch the last practice session, and he ensured that my father, as the heir to the family estate would be there to see my final lessons. But really it was just for form. My father interjected very little.

I was truly fortunate, since my grandfather had me practice everything from Shakkyou (Stone Bridge) and halberd techniques, to Sagi-midare (The Disordered Heron). I had no sense of it at the time, mind you. My grandfather watched over me until he was sure that the building blocks for my career in Noh were firmly in place and then he handed the reins of my teaching over to my father.

Real practice comes from pushing oneself hard

Gensho: At twelve, you’re no longer of an age to take on children’s roles, but neither are you an adult; it’s an awkward, in-between age, though my father continued to make me practice. My voice took forever to break and I was unable to chant properly for the longest time. I’d recite the chants in a voice that wavered between that of a child and that of an adult, but my father instructed me to keep going regardless. That was how he worked and such practice sessions continued until I was in my mid-teens. My father only consented to treat me as an adult actor when I was around fifteen or sixteen years of age.

Uchida: In an earlier time you would have been celebrating the attainment of manhood, wouldn’t you?

Gensho: It was something I guess he was conscious of at the time, true. I know I took on dances that were too advanced for my skill as a performer at the time.

Uchida: Could you give us an example?

Gensho: At sixteen, I danced Hanjo (one of the so-called “kyojo-mono” or mad-woman plays). Thinking back on that time, I’d dearly love to be able to ask my father what on earth he was thinking!

Uchida: I wonder what was behind his thinking?

Gensho: He believed, I think, that I needed to stretch myself as an actor. It’s important to push yourself if you aim to reach the top of any profession; that goes without saying. You must avoid limiting yourself with the notion that a particular role is impossible at a certain age and practice as hard as any adult, because unless you do that practice won’t be of service to you in the future. To be honest, it was hard going, but I got through it and at seventeen was able to perform Dōjō-ji.

Uchida: Dōjō-ji at seventeen! That is an impressive achievement.

Gensho: This is something I learned later in life, but apparently Kita Roppeita XIV – one of the great masters of Noh – also performed Dōjō-ji when he was seventeen, and this was an element in my father’s thinking. I could never hope to reach such consummate levels of performance, mind you. By all accounts, having me perform Dōjō-ji at an early age was one of my grandfather’s last wishes, too. He’d devoted himself to my training and I imagine it’s a role he looked forward to seeing me perform with anticipation. My father thus elected to present Dōjō-ji on the sixth anniversary of my grandfather’s death.

At seventeen, I was still a child. For better or worse, I wasn’t afraid, but I practiced my heart out.

Uchida: You certainly threw yourself heart and soul into that performance (as if jumping into a bell).

Gensho: I assuredly learned that I wasn’t ready to perform in front of strangers. It was a performance undertaken in full awareness of my limitations and afterwards my father said: “Sending you out from behind the entrance curtain was one thing, but I was terribly afraid that you wouldn’t make it back”, in what I imagine was his real feeling on the occasion. He was worried, but I think he realized that Dojo-ji was a necessary rite of passage for my future as a Noh actor.

Added to which, I was a late arrival and wasn’t born until my father was already in his forties. The sons of his contemporaries were, in many cases, already accomplished Noh actors in their twenties. The most senior Noh actor of that generation was Hisao Kanze, who was praised as a genius from a young age. I heard later that this situation was partly the cause of my father’s impatience. He wanted me to be one of this number, which is why, even knowing it was impossible, he wanted me to perform Dōjō-ji at seventeen.

Uchida: Is that so?

Gensho: Once I’d turned twenty, I was treated simply as a professional Noh actor of the Umewaka family and could no longer expect to enjoy the special treatment I’d received as the son of its head. I was already teaching amateur actors by this time, and when I reached the age of twenty-three or twenty-four was told that I should start teaching professionals. It’s an odd way of putting it, but I’d become capable of taking charge of actors who were lacking in insight or perception.

It was my job to find ways of grooming these actors, of turning them into real Noh performers. My father imposed this task on me because he knew I’d learn much from it. I suffered much, though. I had to learn meticulously things about which I had no knowledge and then teach them. If there were things I didn’t understand, I’d ask my father or my elders, or I’d read the written records of Noh plays we had at home. It was at this time that I acquired the habit of reading these texts. My father refused to show me these written records when I was in my teens and I had no urge to read them myself. I wrote down all my father’s words and learned from them.

I began reading these written records in my early twenties, but it was also a form of training. These are ancient texts and are thus open to misreading. Learning to interpret the texts properly so as to avoid any misreading was a discipline I needed to acquire. My early twenties were thus spent learning through asking and learning through reading.

Uchida: It was a time for absorbing knowledge, then?

Gensho: My father then passed away. I was just thirty. Before he died, I was able to gain considerable experience practicing various plays, with the exception of rojomono (a category of Noh plays featuring an old woman as the lead). This was after my father became ill, but the professional actors within the Umewaka fold had reached the age at which they were able to perform difficult plays, including rojomono. Accordingly, as the son of the head of the Umewaka school and its successor I needed to become able to teach the movement patterns on my father’s behalf. My father spoke to me from his sick bed, and I stayed by his bedside in order to learn the kata. It was a very instructive experience.

Some years after my father’s death, when I was in my thirties, I was asked to play the lead in Sotowa Komachi (Komachi on the Stupa), which, if memory serves, is one of the rojomono my father had me practice. I’ve been on my own since then, though have made it thus far thanks to the teachings and assistance of a whole range of people, and I am deeply grateful to them all. (End of Part 2)

May 18, 2015

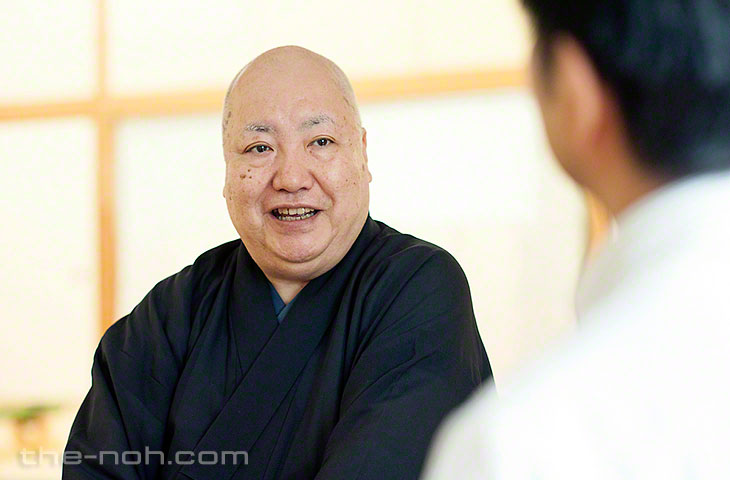

Gensho Umewaka (梅若玄祥), a principal actor of the Kanze School and current head of the Umewaka family

Born 1948 (Showa 23), Gensho made his first stage appearance as a child in 1951 (Showa 26) in Kurama-Tengu. Gensho assumed the name of Rokuro Umewaka LVI in 1988 (Showa 63); changing his name to Gensho Umewaka II in 2008 (Heisei 20).

Today he is a popular and accomplished lead actor. Gensho works actively to revive near-forgotten works and stage unique new ones, and his willingness to attempt different staging styles is helping to keep the classical Noh tradition alive and well. He is eager to introduce Noh to foreign audiences and besides staging the first international exhibition of Noh masks and costumes, has performed in America, France, the Netherlands and Russia. He is one of the pioneers in the effort to bring Noh to auditoriums. He is admired both inside and outside the world of Noh and by artists the world over as one of the rare individuals who looks upon every meeting as a fortuitous event. Gensho has been designated an Important Intangible Cultural Property of Japan and is on the executive board of The Japan Art Academy, Association for Japanese Noh Plays, and the Japan Theater Arts Association. He is president of the Umewaka Noh Theater Association and director of the Umewaka Noh Theater, and is representative of the Noh project “Koroku”.

Interviewer: Takahiro Uchida (内田高洋), the-Noh.com

Uchida entered the Noh club of the Hosho School at Kyoto University and became captivated by the art there. Since then, watching plays and learning about all aspects of Noh, he has practiced singing and dancing with the Hosho School as well as playing fue (flute) at the Morita School and taiko (stick drum) at the Kadono School. He also writes and edits the Hosho newsletter of the Hosho School.