Interview

Interview

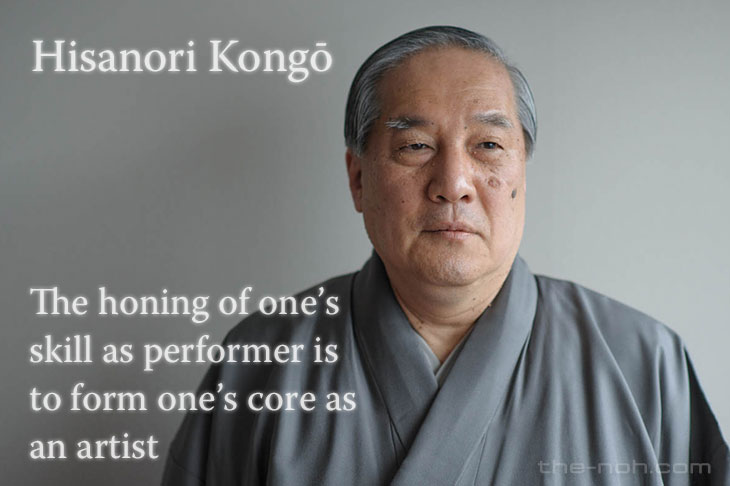

One day last year (2016), I made my way to the Kongō Noh Theatre at Nakadachiuri Agaru on Karasuma-dori to the west side of the Kyoto Imperial Palace, to pay a call on Hisanori Kongō.

The rain had lifted and suffused in soft sunlight the Noh theatre had an air of quietness and serenity. Welcoming me between callers, the head of the Kongō school had all the self-possessed softness and dignity one would expect of a family head.

Displaying an inherent sincerity and artlessness in conversation, Hisanori Kongō spoke eloquently about the Kongō school, the magic of Noh and noh theater, before moving on to discuss matters of import to the world of Noh and what constitutes the essence of Noh artistry. (March 2, 2017)

![]() Part 1: Tips on enjoying a Noh performance

Part 1: Tips on enjoying a Noh performance

![]() Part 2: A history as a performer marked by a respect for the basic techniques

Part 2: A history as a performer marked by a respect for the basic techniques

Interviewer: Takahiro Uchida, the-Noh.com / Photos: Shigeyoshi Ohi

Part 1: Tips on enjoying a Noh performance

The Kongō school of Noh

Uchida: Since many visitors to “The-noh.com” are new to the world of Noh, would you mind giving us a brief history of the Kongō school and explaining its salient characteristics?

Kongō: The Kongō school is also referred to as “Mai-Kongō” (literally, “Dancing Kongō”) and is renowned for the liveliness and visually dynamic movement segments (kata) performed by its actors. In historical terms, during the Genroku years (1688-1704) of the Edo period, the school was headed by a man named Matabei Nagayori (1662-1700). Popularly known as “Light-footed Matabei”, he was especially famous for his rapid footwork, but by all accounts the characteristics of the Kongō style have intensified since his time. Tadaichi Ukon, the 20th-generation head, is credited for developing the idea for the thousand silken threads (spider silk) that are used in Tsuchigumo (Ground Spider), which became a drawing card for the Kongō school and has since found its way into kabuki and into other schools of Noh.

Another master of the Kongō school was Hyōe no jō Ujimasa (1507-76), who lived during the Sengoku period – the age of provincial wars in Japan – and went by the name of “Hana Kongō” (literally, “Nose Kongō”).

Going even further back in time, the origins of the Kongō style of Noh can be traced back to the Sakado-za group, which served the temple of Hōryū (in Nara Prefecture). There are references to the Kongō style in the literature of Hōryū Temple dating from the Kamakura period (1155-1333), and as one of the Sarugaku groups it has a long and ancient history. The school was later attached to Kasuga Taisha (Kasuga Grand Shrine) and Kōfuku-ji (Kōfuku Temple, Nara Prefecture), when it became one of the four Yamato theatrical groups (dance troupes that played before the Gods).

Let me tell you the legend of how the Sakado-za came to be known as the Kongō-za. The Kongō family name is said to date back to the time of the grand master Saburō-Masaaki (1449-1529). Saburō had an older brother and he reportedly intended to carry on the Sakado-za lineage. Saburō entered the priesthood, joining a temple on Mount Kongō, which lay on the provincial border between Yamato (corresponding to present-day Nara Prefecture) and Kawachi (the eastern part of modern Osaka). Unfortunately, the older brother with plans to take over as the head of the Sakado-za died making Saburō the heir to the troupe, and the Kongō-za appellation came into being upon his return from Mount Kongō.

Today, I am continuing the Kongō lineage as its 26th-generation family head, but in order to keep the head-of-family tradition of the four Yamato-za groups alive, historically, the groups have taken in the sons of other schools as adopted disciples and sent their own sons for adoption by other members of the Yamato-za. In olden times, it was the custom, upon entering another school as an adopted disciple, to take a play from your original school with you. The Hōshō school, for example, has had two family heads who were adopted as disciples from the Kongō school, one of whom took Shakkyō (Stone Bridge) – Renjishi, (the lion dance danced by two lions) with him, whilst the other took Makiginu (The Rolls of Silk).

During a certain period, the Kongō school did not perform Shakkyō, whilst the only remaining version of Makiginu forms part of the godan kagura (literally, “five-stage god-entertainment”)*, and the standard version of this play is no longer performed. Today, when I see a Hōshō school performance of Makiginu, I see vestiges of the Kongō style of Noh.

Uchida: Shakkyō (Renjishi) is held in particularly high esteem by the Hōshō school, is it not?

Kongō: Shakkyō itself was revived by the Kongō school, but the lion dance – Renjishi – was presented to the Hōshō family, and it is now performed as Shakkyo Wago-renjishi, or “The Stone Bridge featuring two lions”.

Uchida: It’s a gift of sorts, which is a fascinating custom when you come to think of it.

* In Noh, “kagura” refers to a sacred dance of divine appeasement that is performed by shrine maidens or gods in the body of a woman. There are distinct differences in the flute melodies –the way in which the flute is performed – in so-called “common kagura” and that of godan kagura.

The highlight of Wago-renjishi is the aimai dance featuring a red lion and a white lion. Performed on November 24, 2013.

In Makiginu (The Rolls of Silk) as performed by the Kongō school, all five sections (godan) are performed as kagura or sacred dances.

The all-new, time-honored Kongō Noh Theatre

Uchida: Many years ago when I was a student, my fellows and I rented the Kongō Noh Theatre when it was still located to the north of Shijo Muramachi (Kyoto) and gave a student performance of Noh; I danced the shimai, as I recall, and also sang a rengin – a scene in which two or more actors sing together. It was a lovely stage, wooden, with a very calm atmosphere to it.

I’m told that the relocation of the Kongō Noh Theatre was a laborious process, but I wonder if you’d be kind enough to give us some background to the move.

Kongō: It’s been thirteen years since we moved to our current location. The reason for the move was the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake (of January 17, 1995). The earthquake caused the theatre to tilt and having called in surveyors we learned that it was in a hazardous condition. Various measures were put forward, including rebuilding the theatre, but the previous location had a very narrow frontage compared to the depth of the site and was in violation of Fire Defense Law, which effectively ruled out both the repair and rebuild options. The initial plan called for the creation of a purpose-built building with our neighbors that would have had a wider frontage, but we ultimately decided to go with a new location and moved here.

Uchida: You now have an extremely refined location facing the Kyoto Imperial Palace; was it easy to find this spot?

Kongō: By no means, we did the rounds of numerous sites before we found our current location. It was originally part of the vast Imperial residence, but we had a stroke of good fortune. We were extremely lucky in our connections, I have to say.

Uchida: Personally speaking, the dismantling and reconstruction of the original stage conjures fond memories of the calm atmosphere of the old Kongō Noh Theatre, but with its new lighting and other innovations, you have created what constitutes a magnificent addition to Kyoto’s Noh resources.

Kongō: It is a tribute to our relations with many, many people, and we are hugely indebted to their efforts on our behalf.

The appeal of the Kongō Noh Theatre, which combines the elegance of Kyoto with state-of-the-art equipment

- It’s highly desirable location overlooking the Kyoto Imperial Palace and its readily accessible entranceway;

- The relocation of the old Noh theatre and its quiet stage that has a history dating back to the Meiji era woven into its very fabric;

- The introduction of “Earphone Guides” (providing essential translation of lyrics, as well as explanations relating to the stories, music, dance, actors, properties and other aspects of Noh that may be difficult for non-Japanese visitors to understand), with six-channel simultaneous translation equipment;

- The use of colored lighting, a first in Noh theatre;

- An innovative interior that incorporates natural light and the beauty of the atmosphere generated by the gardens, etc.

The Kongō school is the only one of the Noh shite-kata schools to be based in Kyoto. The stage was brought from the former Kongō Noh Theatre and reassembled at its new location to the west of Kyoto Imperial Palace.

Besides the traditional wave crest pattern seigaiha decorating the walls of the hashigakari (the bridge-like walkway to the main stage), the bamboo blinds and sliding paper screens provide a touch of elegance.

Bringing Noh to a wider audience

Uchida: The Kongō Noh Theatre serves as the base for regular Noh performances and for numerous other events, and is providing opportunities for many people to enjoy the theatrical art of Noh. It’s widely held that Noh has fallen on hard times of late; may I ask what efforts you are making to bring Noh to a wider audience?

Kongō: In the first instance, I believe it’s never too soon to bring people into contact with Noh, young people especially. We have projects that introduce Noh to elementary, junior high and high school students, and I lead a course on Noh at Kyoto City University of Arts.

Uchida: Is Noh on the university curriculum?

Kongō: It’s taught by the Faculty of Music at the university and many of those students are looking to become elementary and junior high school teachers. Japanese music classes are part of the compulsory music curriculum, and the University of Arts wanted to include Noh chants in the syllabus so it has been added to the core teacher-training program. There is also a club that I’ve been attending for more than a decade where members practice the art of Noh. The club is interesting in that most of its members are liberal arts students as opposed to professional musicians, though that is probably because the gap between Noh and the Western music they are used to studying is too wide.

The only university to offer Noh as part of its Japanese music syllabus is Tokyo University of the Arts (Geidai), and it would be good to see more public universities in Kyoto and Aichi and elsewhere serving as strongholds for Japanese music, though perhaps the relocation of Kyoto City University of Arts* will trigger moves in that direction; I certainly hope so.

Uchida: It would be nice to see a cultural administration policy devoted to Japanese classics, would it not? What other efforts are you making to increase Noh’s popularity.

Kongō: One of the biggest changes from the past is the drop off in the number of people taking lessons in Noh chanting. The Kongō school benefits from its Kyoto location in that Kyoto values its traditional cultural heritage and the connections still exist, so there are a number of students who come because their parents did. But whilst there are fewer enthusiasts for Noh chanting as a study, the number of people who come to see Noh performances as theatre is on the increase. As I see it, the key to the issue is to increase the Noh viewing opportunities available to men and women of all ages, both Japanese and foreign and from all walks of life. We have recently begun providing commentary ahead of performances with a view to facilitating the understanding of our audiences.

Uchida: A little ingenuity goes a long way, and your unflagging commitment to prompting Noh is really the only way forward.

Kongō: We stage a candlelit Noh performance to coincide with the Daimonji Gozan Okuribi (Daimonji Bonfire) in August, and this year borrowed the stage at Higashi Honganji Temple for regular Noh performances in order to add a little variety to our program, but we need to look to the future, too.

* Kyoto City University of Arts prides itself on a long history that dates back more than 130 years. The decision has been taken to move the existing university from its present location in Nishikyō-ku to the Sūjin area to the east of Kyoto station that serves as the gateway to the city in the hope that it will contribute to the growth of Kyoto as a center for culture and the fine arts.

Candlelit Noh performances are staged on August 16 every year, the day of the Daimonji Gozan Okuribi (Daimonji Bonfire). The colored lights that were installed following the relocation of the Kongō Noh Theatre create a world of distinctively delicate beauty. Photo taken August 16, 2009 during a performance of Aya no Tsuzumi (The Damask).

Hisanori Kongō performing Kurama-tengu (Long-nosed Goblin in Kurama) at Higashi Honganji (the Eastern Temple of the Original Vow) in Kyoto on April 24, 2016.

It’s okay to nod off during a Noh performance

Uchida: I realize that, from a performer’s perspective, there are many aspects of Noh that are difficult to put into words, but could you give our readers some insight into the appeal of Noh?

Kongō: Noh plays can be difficult to follow for a first-time viewer, and whilst there are plays like Tsuchigumo (Ground Spider) that are more readily accessible, many of the plays are difficult to understand. A good way to develop an interest is to start by focusing on a single aspect of the performance that appeals to you. Devoting your full attention to the sound of the instruments, for example, or focusing on the expressions of the Noh masks, the color of the costumes, or the music of the chants; anything you like, really. With repeated viewing, the smallest of openings will alter your experience of Noh performances and make them more interesting and enjoyable.

I’m an opera lover and often go to see performances, but there’s a sense that the impressiveness of the orchestra is being used to stun audiences into wonder, I think. Noh, on the other hand, is at the opposite end of the spectrum: it draws the viewer in.

Uchida: The seeming incomprehensibility of Noh can produce an adverse reaction in some viewers, but knowing that it’s baffling at first could actually be reassuring for people who are new to this world, don’t you think?

As an amateur who is fascinated by Noh, I think it’s a great pity that there are people who know nothing of this performing art and would love to see more people become acquainted with the richness of its allure. As you so rightly pointed out just now, finding a way in – something to focus on when watching a performance, and working from there towards a greater appreciation of this theatrical art is a surefire way of increasing the number of people who enjoy Noh.

There’s something to be said for trying your hand at Noh, too, isn’t there?

Kongō: There are significant obstacles that need to be overcome if, for example, you want to sing an aria from an opera or dance a ballet, but even an amateur – someone with no experience whatsoever – can enjoy Noh chanting and dancing. Taking a class in Noh is an excellent way of increasing the interest and enjoyment of watching a Noh performance.

Uchida: Even an amateur can don a Noh mask, put on a Noh costume, and dance. That’s very enticing and I’ve done it myself; it’s the door to a whole new world of experience.

Kongō: It’s certainly quite unique, and it’s this that makes Noh so interesting.

It’s perfectly acceptable to doze off during a Noh performance. There’s no need to panic if you can’t fathom what’s going on or to over exert yourself in trying to understand what’s happening; a more gradual approach is the way to enjoyment since the appeal of Noh is something that reveals itself over time.

Uchida: This is a common misconception, but there are in fact no hard and fast rules to enjoying a Noh performance, are there?

Kongō: That’s true. It’s more important to feel your way in. Knowing something about the story before you go will help you to understand what you’re seeing and it’s a good way to prepare for watching a Noh performance. Noh stories are highly structured and many have intricate, complex storylines that merit slow enjoyment. The world as portrayed by Noh is definitely worth seeing and I hope your readers will be encouraged by this to go and see a live performance. (End of Part 1) ![]()

Hisanori Kongō(金剛永謹), 26th-generation head of the Kongō School of shite-kata (lead actors)

Born in Kyoto in 1951 as the eldest son of Iwao Kongō, the 25th-generation Grand Master of the Kongō school. He began studying under his father in early childhood, making his stage debut at the age of four and his first appearance as the shite at six years of age. He is a holder of important intangible cultural heritage (collective recognition). On September 18, 1998, he succeeded his father to become the 26th-generation Grand Master of the Kongō school. Hisanori Kongō is acclaimed for bringing the refinement and elegance of Kyoto to the Kongō style of Noh, which is known as “Mai-Kongō” (or “Dancing Kongō”) and is renowned for its uniquely flamboyant and dynamic style. Of the five shite-kata family heads, he is the only one to be based in the Kansai region. 2003 saw the completion of work to relocate the Kongō Noh Theatre from its former location in Shijo Muramachi to the west side of the Kyoto Imperial Palace. Beginning with Canada and North America, Hisanori Kongō has toured overseas a number of times as the head of a troupe of Noh performers, performing in Italy, Spain, France, Portugal and elsewhere.

He is the recipient of the Kyoto Municipal New Artist Award (1984), the Kyoto Prefectural Culture Award’s New Artist Prize (1986) and the Kyoto Prefectural Culture Award’s Person of Cultural Merit (2004). In 2010, he received an Order of Merit for Distinguished Service to Culture from Kyoto City.

He is managing director of the Nihon Nohgaku-kai, President of the Kongōkai, and President of the Kongō Nohgakudo Foundation, as well as a visiting professor at the Kyoto City University of Arts and the Doshisha University. He is the author of a work entitled “Kongō-ke no Men” (“The Mask of the Kongō Family”)

Interviewer: Takahiro Uchida (内田高洋), the-Noh.com

Uchida entered the Noh club of the Hosho School at Kyoto University and became captivated by the art there. Since then, watching plays and learning about all aspects of Noh, he has practiced singing and dancing with the Hosho School as well as playing fue (flute) at the Morita School and taiko (stick drum) at the Kadono School. He also writes and edits the Hosho newsletter of the Hosho School.